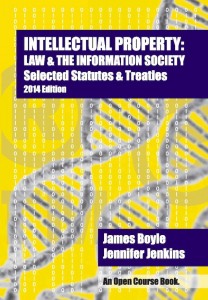

Jennifer Jenkins and I are frantically working to put together a new open casebook on Intellectual Property Law. (It will be available, in beta version, this Fall under a CC license, and freely downloadable in multiple formats of course. Plus it should sell in paper form for about $130 less than the competing casebooks. The accompanying statutory supplement will be 1/5 the price of most statutory supplements — also freely downloadable.) More about that later. While assembling the materials for a casebook, one gets to revisit the archives, reread the great writers. Today I was revisiting Victor Hugo. Hugo was a fabulous — inspiring, passionate — proponent of the rights of authors, and the connection of those rights to free expression and free ideas. He went beyond giving speeches to play a serious role in setting up the current international copyright system. He is held out today as the ultimate proponent of the droits d’auteur — the person who said (and he did) that the author’s right was the most sacred form of property: unlike other property rights it impoverished no one, because it was over something that was entirely new. (Think of Locke and his point that all property took from the common store. Not so with copyright, said Hugo) But Hugo was a more subtle fellow than that and his views are not what you may have been told they were. I decided to translate his speech to the Congress of Literary, Industrial and Artistic Property in Paris in 1878. (There’s probably a better translation out there — I just couldn’t find it.) And I was struck, as if for the first time, by what he said about the need to create a system that respected not just the rights of authors. but the public’s rights, the public’s ownership of the public domain.

Victor Hugo, guardian of the public domain and a proponent of the exact kind of right of the public to the public domain that Justice Ginsburg found so incomprehensible in Golan v. Holder.

Here is an excerpt. For those of you impatient to cut to the chase, the bolded section at the end gives Hugo’s views on the public domain. [NB: this is a free translation — Hugo was a florid speaker. I’ve tried to reproduce the force of his speech using italics and other forms of emphasis that are not in the original. And of course the bolded section is courtesy of me. Lector beware]

Excerpts from the speech of Victor Hugo to the Congress of Literary, Industrial and Artistic Property, Paris, 1878. [Emphases added]

Literary property is of general utility.

All the old monarchical laws denied and still deny literary property. For what purpose? For the purpose of control. The writer-owner is a free writer. To take his property, is to take away his independence. One wishes that it were not so. [That is the danger in] the remarkable fallacy, which would be childish if it were not so perfidious, “thought belongs to everyone, so it cannot be property, so literary property does not exist.” What a strange confusion! First, to confuse the ability to think, which is general, with the thought, which is individual; my thought is me. Then, to confuse thought, an abstract thing, with the book, a material thing. The thought of the writer, as thought, evades the grasping hand. It flies from soul to soul; it has this gift and this force — virum volitare per ora — that it is everywhere on the lips of men. But the book is distinct from the thought; as a book, it is “seizable,” so much so that it is sometimes “seized.” [impounded, censored, pirated.] (Laughter.)

The book, a product of printing, belongs to industry and is the foundation, in all its forms, of a large commercial enterprise. It is bought and sold; it is a form of property, a value created, uncompensated, a form of riches added by the writer to the national wealth. Indeed, all must agree, this is the most compelling form of property.

Despotic governments violate this property right; they confiscate the book, hoping thus to confiscate the writer. Hence the system of royal pensions. [Pensions for writers, in the place of author’s rights] Take away everything and give back a pittance! This is the attempt to dispossess and to subjugate the writer. One steals, and then one buys back a fragment of what one has stolen. It is a wasted effort, however. The writer always escapes. We became poor, he remains free. (Applause) Who could buy these great minds, Rabelais, Molière, Pascal? But the attempt is nonetheless made , and the result is dismal. Monarchic patronage sucks at the vital forces of the nation. Historians give Kings the title the “father of the nation” and “fathers of letters;….. the result? These two sinister facts: people without bread, Corneille [the great French author] without shoes. (Long applause).

Gentlemen, let us return to the basic principle: respect for property. Create a system of literary property, but at the same time, create the public domain! Let us go further. Let us expand the idea. The law could give to all publishers the right to publish any book after the death of the author, the only requirement would be to pay the direct heirs a very low fee, which in no case would exceed five or ten percent of the net profit. This simple system, which combines the unquestionable property of the writer with the equally incontestable right of the public domain was suggested by the 1836 commission [on the rights of authors]; and you can find this solution, with all its details, in the minutes of the board, then published by the Ministry of the Interior.The principle is twofold, do not forget. The book, as a book, belongs to the author, but as a thought, it belongs – the word is not too extreme – to the human race. All intelligences, all minds, are eligible, all own it. If one of these two rights, the right of the writer and the right of the human mind, were to be sacrificed, it would certainly be the right of the writer, because the public interest is our only concern, and that must take precedence in anything that comes before us. [Numerous sounds of approval.]But, as I just said, this sacrifice is not necessary.

I am against the idea of a “paying public domain” — but I will note that Hugo’s proposal is many ways more radical than any current orphan works legislation. Not just in its details — replacing property rule with liability rule — but in its premises, which people often forget. Yes, he was relying on the familiar idea-expression distinction, which no American lawyer would deny. The author owns the expression. The public gets free access to the idea. And this is in fact one of the most brilliant parts of our copyright system. But look more closely. He was also firmly resting intellectual property on a public interest foundation and he was focused on access to the public domain — to the actual expression, the books, not just idea — front and center. That is why he suggests the idea of any publisher being able to reprint any book. Would that we had such a system for orphan works — even if not for works in the public domain. Here, by contrast, is Justice Ginsburg who — we are told — comes from a society with a more moderate, balanced, and less absolute form of copyright… She is writing the majority opinion in a case about taking works out of the public domain and putting them back under copyright.

As petitioners put it in this Court, Congress impermissibly revoked their right to exploit foreign works that “belonged to them” once the works were in the public domain. To copyright lawyers, the “vested rights” formulation might sound exactly backwards: Rights typically vest at the outset of copyright protection, in an author or rightholder. See, e.g., 17 U.S.C. § 201(a) (“Copyright in a work protected . . . vests initially in the author. . . .”). Once the term of protection ends, the works do not revest in any rightholder. Instead, the works simply lapse into the public domain. See, e.g., Berne, Art. 18(1), 828 U.N.T.S., at 251 (“This Convention shall apply to all works which . . . have not yet fallen into the public domain. . . .”). Anyone has free access to the public domain, but no one, after the copyright term has expired, acquires ownership rights in the once-protected works.

But perhaps there are forms of public right other than ownership. Hugo understood that point. It is a shame we no longer do so. ” If one of these two rights, the right of the writer and the right of the human mind, were to be sacrificed, it would certainly be the right of the writer, because the public interest is our only concern, and that must take precedence in anything that comes before us. [Numerous sounds of approval.]But, as I just said, this sacrifice is not necessary.” But what of the cases — orphan works are only one example — where the author gets nothing, but the public is impoverished?

Back to writing the casebook!