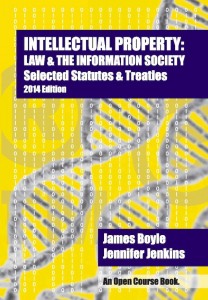

We are posting excerpts from our new coursebook Intellectual Property: Law and the Information Society which will be published in two weeks is out now! It will be is of course freely downloadable, and sold in paper for about $135 less than other casebooks. (And yes, it will include discussions of whether one should ever use the term “intellectual property.” ) The book is full of practice examples.. This is one from Chapter One, on the theories behind intellectual property: “What if you came up with the idea of Fantasy Football?” No legal knowledge necessary. Why don’t you test your argumentative abilities…?

(Book Coming Soon! Book Out now! Needless to say, in this and all exercises in the book, the facts are either entirely made up or significantly altered to generate a better discussion]

Problem 1-2

Justifying and Limiting.

It is early in the days of the web and you and your friends have just had a great idea. You are avid football fans, fond of late night conversations about which team is really the best, which player the most productive at a particular position. Statistics are thrown about. Bragging is compulsory. Unlike other casual fans, you do not spend all your time rooting for a particular team. Your enjoyment comes from displaying your knowledge of all the players and all the teams, using statistics to back up your claims of superiority and inferiority. You find these conversations pleasant, but frustrating. How can one determine definitively who wins or loses these debates? Then you have a collective epiphany. With a computer, the raft of statistics available on football players could be harvested to create imaginary teams of players, “drafted” from every team in the league, that would be matched against each other each week according to a formula that combined all the statistics into a single measure of whether your team “won” or “lost” as against all your friends’ choices. By adding in prices that reflected how “expensive” it was to choose a particular player, one could impose limits on the tendency to pick a team composed only of superstars. Instead, the game would reward those who can find the diamond in the rough, available on the cheap, who know to avoid the fabled player who is actually past his best and prone to injury.

At first, you gather at the home of the computer-nerd in your group, who has managed to write the software to make all this happen. Then you have a second epiphany. Put this online and everyone could have their own team—you decide to call them FANtasy Football Teams, to stress both their imaginary nature and the intensity of the football-love that motivates those who play. Multiple news and sports sites already provide all the basic facts required: the statistics of yardage gained, sacks, completed passes and so on. The NFL offers an “official” statistics site, but many news outlets collect their own statistics. It is trivial to write a computer program to look up those statistics automatically and drop them into the FANtasy game. Even better, the nature of a global network makes the markets for players more efficient while allowing national and even global competition among those playing the game. The global network means that the players never need to meet in reality. FANtasy Football Leagues can be organized for each workplace or group of former college friends. Because the football players you draft come from so many teams, there is always a game to keep track of and bragging to be done on email or around the water cooler.

FANtasy Football is an enormous success. You and your friends are in the middle of negotiations with Yahoo! to make it the exclusive FANtasy Football League network, when you receive a threatening letter from the NFL. They claim that you are “stealing” results and statistics from NFL games, unfairly enriching yourself from an activity that the league stages at the cost of millions of dollars. They say they are investigating their legal options and, if current law provides them no recourse, that they will ask Congress to pass a law prohibiting unlicensed fantasy sports leagues. (Later we will discuss the specific legal claims that might actually be made against you under current law.) As this drama is playing out, you discover that other groups of fans have adapted the FANtasy Football idea to baseball and basketball and that those leagues are also hugely popular.

i.) Your mission now is to lay out the ethical, utilitarian or economic arguments that you might make in support of your position that what you are doing should not be something the NFL can control or limit—whether they seek to prohibit you, or merely demand that you pay for a license. What might the NFL say in support of its position or its proposed law?

ii.) Should you be able to stop the “copycat” fantasy leagues in baseball and basketball? To demand royalties from them? Why? Are these arguments consistent with those you made in answer to question i.)? Read the Locke excerpt (below) before you answer the questions.

John Locke, Of Property

Two Treatises on Government

§ 26. Though the earth and all inferior creatures be common to all men, yet every man has a “property” in his own “person.” This nobody has any right to but himself. The “labour” of his body and the “work” of his hands, we may say, are properly his. Whatsoever, then, he removes out of the state that Nature hath provided and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with it, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property. It being by him removed from the common state Nature placed it in, it hath by this labour something annexed to it that excludes the common right of other men. For this “labour” being the unquestionable property of the labourer, no man but he can have a right to what that is once joined to, at least where there is enough, and as good left in common for others.

§ 27. He that is nourished by the acorns he picked up under an oak, or the apples he gathered from the trees in the wood, has certainly appropriated them to himself. Nobody can deny but the nourishment is his. I ask, then, when did they begin to be his? when he digested? or when he ate? or when he boiled? or when he brought them home? or when he picked them up? And it is plain, if the first gathering made them not his, nothing else could. That labour put a distinction between them and common. That added something to them more than Nature, the common mother of all, had done, and so they became his private right. And will any one say he had no right to those acorns or apples he thus appropriated because he had not the consent of all mankind to make them his? Was it a robbery thus to assume to himself what belonged to all in common? If such a consent as that was necessary, man had starved, notwithstanding the plenty God had given him. We see in commons, which remain so by compact, that it is the taking any part of what is common, and removing it out of the state Nature leaves it in, which begins the property, without which the common is of no use. And the taking of this or that part does not depend on the express consent of all the commoners. Thus, the grass my horse has bit, the turfs my servant has cut, and the ore I have digged in any place, where I have a right to them in common with others, become my property without the assignation or consent of anybody. The labour that was mine, removing them out of that common state they were in, hath fixed my property in them. . . .

§ 29. Thus this law of reason makes the deer that Indian’s who hath killed it; it is allowed to be his goods who hath bestowed his labour upon it, though, before, it was the common right of every one. And amongst those who are counted the civilised part of mankind, who have made and multiplied positive laws to determine property, this original law of Nature for the beginning of property, in what was before common, still takes place, and by virtue thereof, what fish any one catches in the ocean, that great and still remaining common of mankind; or what amber-gris any one takes up here is by the labour that removes it out of that common state Nature left it in, made his property who takes that pains about it. And even amongst us, the hare that any one is hunting is thought his who pursues her during the chase. For being a beast that is still looked upon as common, and no man’s private possession, whoever has employed so much labour about any of that kind as to find and pursue her has thereby removed her from the state of Nature wherein she was common, and hath begun a property.

§ 30. It will, perhaps, be objected to this, that if gathering the acorns or other fruits of the earth, etc., makes a right to them, then any one may engross as much as he will. To which I answer, Not so. The same law of Nature that does by this means give us property, does also bound that property too. “God has given us all things richly.” Is the voice of reason confirmed by inspiration? But how far has He given it us “to enjoy”? As much as any one can make use of to any advantage of life before it spoils, so much he may by his labour fix a property in. Whatever is beyond this is more than his share, and belongs to others. Nothing was made by God for man to spoil or destroy. And thus considering the plenty of natural provisions there was a long time in the world, and the few spenders, and to how small a part of that provision the industry of one man could extend itself and engross it to the prejudice of others, especially keeping within the bounds set by reason of what might serve for his use, there could be then little room for quarrels or contentions about property so established.

§ 31. But the chief matter of property being now not the fruits of the earth and the beasts that subsist on it, but the earth itself, as that which takes in and carries with it all the rest, I think it is plain that property in that too is acquired as the former. As much land as a man tills, plants, improves, cultivates, and can use the product of, so much is his property. He by his labour does, as it were, enclose it from the common. Nor will it invalidate his right to say everybody else has an equal title to it, and therefore he cannot appropriate, he cannot enclose, without the consent of all his fellow-commoners, all mankind. God, when He gave the world in common to all mankind, commanded man also to labour, and the penury of his condition required it of him. God and his reason commanded him to subdue the earth—i.e., improve it for the benefit of life and therein lay out something upon it that was his own, his labour. He that, in obedience to this command of God, subdued, tilled, and sowed any part of it, thereby annexed to it something that was his property, which another had no title to, nor could without injury take from him.

§ 32. Nor was this appropriation of any parcel of land, by improving it, any prejudice to any other man, since there was still enough and as good left, and more than the yet unprovided could use. So that, in effect, there was never the less left for others because of his enclosure for himself. For he that leaves as much as another can make use of does as good as take nothing at all. Nobody could think himself injured by the drinking of another man, though he took a good draught, who had a whole river of the same water left him to quench his thirst. And the case of land and water, where there is enough of both, is perfectly the same.

§ 33. God gave the world to men in common, but since He gave it them for their benefit and the greatest conveniencies of life they were capable to draw from it, it cannot be supposed He meant it should always remain common and uncultivated. He gave it to the use of the industrious and rational (and labour was to be his title to it); not to the fancy or covetousness of the quarrelsome and contentious. He that had as good left for his improvement as was already taken up needed not complain, ought not to meddle with what was already improved by another’s labour; if he did it is plain he desired the benefit of another’s pains, which he had no right to, and not the ground which God had given him, in common with others, to labour on, and whereof there was as good left as that already possessed, and more than he knew what to do with, or his industry could reach to.

§ 34. It is true, in land that is common in England or any other country, where there are plenty of people under government who have money and commerce, no one can enclose or appropriate any part without the consent of all his fellow commoners; because this is left common by compact—i.e., by the law of the land, which is not to be violated. And, though it be common in respect of some men, it is not so to all mankind, but is the joint propriety of this country, or this parish. Besides, the remainder, after such enclosure, would not be as good to the rest of the commoners as the whole was, when they could all make use of the whole; whereas in the beginning and first peopling of the great common of the world it was quite otherwise. The law man was under was rather for appropriating. God commanded, and his wants forced him to labour. That was his property, which could not be taken from him wherever he had fixed it. And hence subduing or cultivating the earth and having dominion, we see, are joined together. The one gave title to the other. So that God, by commanding to subdue, gave authority so far to appropriate. And the condition of human life, which requires labour and materials to work on, necessarily introduce private possessions.

Questions:

1.) Which side in Problem 1-2 can appeal to Locke’s arguments? The NFL? The FANtasy Football Players? Both? Find the passage that supports your answers.

2.) Should Locke’s argument apply to information goods? Why? Why not?

3.) Locke talks about a realm that is “left common by compact.” What does this consist of in the realm of information? Would Locke imagine that private property needs to be introduced to the “great common” of the information world, just as it was to the wilderness?