I teach at Duke University, an institution I love. The reverse may not be true however, at least after my most recent paper (with Jennifer Jenkins) — Mark of the Devil: The University as Brand Bully. (forthcoming in the Fordham Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law Journal). The paper is about the university most frequently accused of being a “trademark bully” — an entity that makes assertions and threats far beyond what trademark law actually allows, something that is all too common, with costs to both competition and free speech. Unfortunately, that university is our own — Duke.

For years, online rankings have Duke near the top of the charts for trademark bullying — not as compared to other universities, as compared to all companies doing business in the US. Here are 4 years of rankings from the website “Trademarkia.” As you can see, Duke is second only to the famously litigious Monster Energy Company. (Duke’s rank fell to #8 last year, which was good news. Unfortunately, one reason is that oppositions have risen overall rather than merely that Duke’s have declined.)

But what are these online rankings based on? The methodologies are not transparent and the easiest methods — for example, counting how many times an entity opposed the registration of another company’s trademark — are obviously flawed. If Nike opposes more trademarks than Boyle’s House of Brisket, we shouldn’t be surprised.

But what are these online rankings based on? The methodologies are not transparent and the easiest methods — for example, counting how many times an entity opposed the registration of another company’s trademark — are obviously flawed. If Nike opposes more trademarks than Boyle’s House of Brisket, we shouldn’t be surprised.

Jennifer Jenkins and I teach intellectual property — including trademark — at Duke Law School. We had seen these stories. Indeed, colleagues from other law schools would tease us about them, but we were skeptical. In the areas we knew about — copyright or fair use policy, for example — Duke was actually very enlightened. Eventually, our interest was piqued so much that we conducted what is, so far as we know, the first empirical study of the trademark assertion practice by a university. We thought it might well show Duke’s innocence of the bullying charge. Umm.. Not so much.

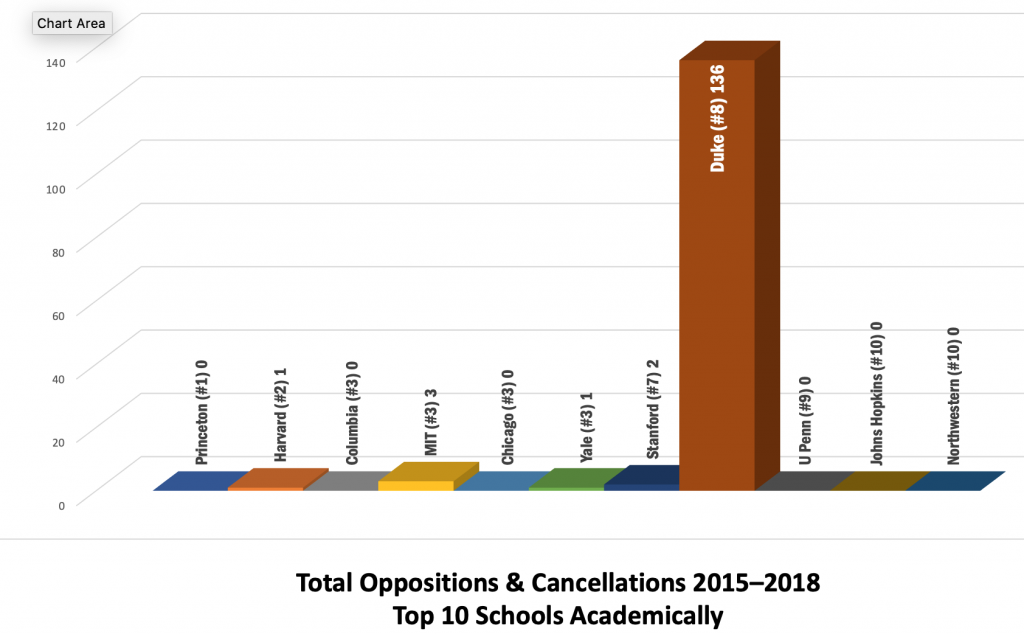

Our empirical study was divided into two parts: The Comparative Study and the Merit Study. We focused on “oppositions” and “cancellations” — the process by which a trademark owner objects to someone filing a new mark, because they think it is too close to their own or attempts to cancel a mark that had been granted. importantly, both challenges occur after a PTO examiner has concluded that the new mark does not appear to be likely to cause confusion. In the Comparative Study we tried to find endogenous variables that might explain disparate rates of trademark oppositions. Perhaps academically elite institutions had lots of parasites and free riders eager to file marks that cut a little too close to the names or logos of famous colleges. Thus we compared Duke to the top ten academically ranked institutions.

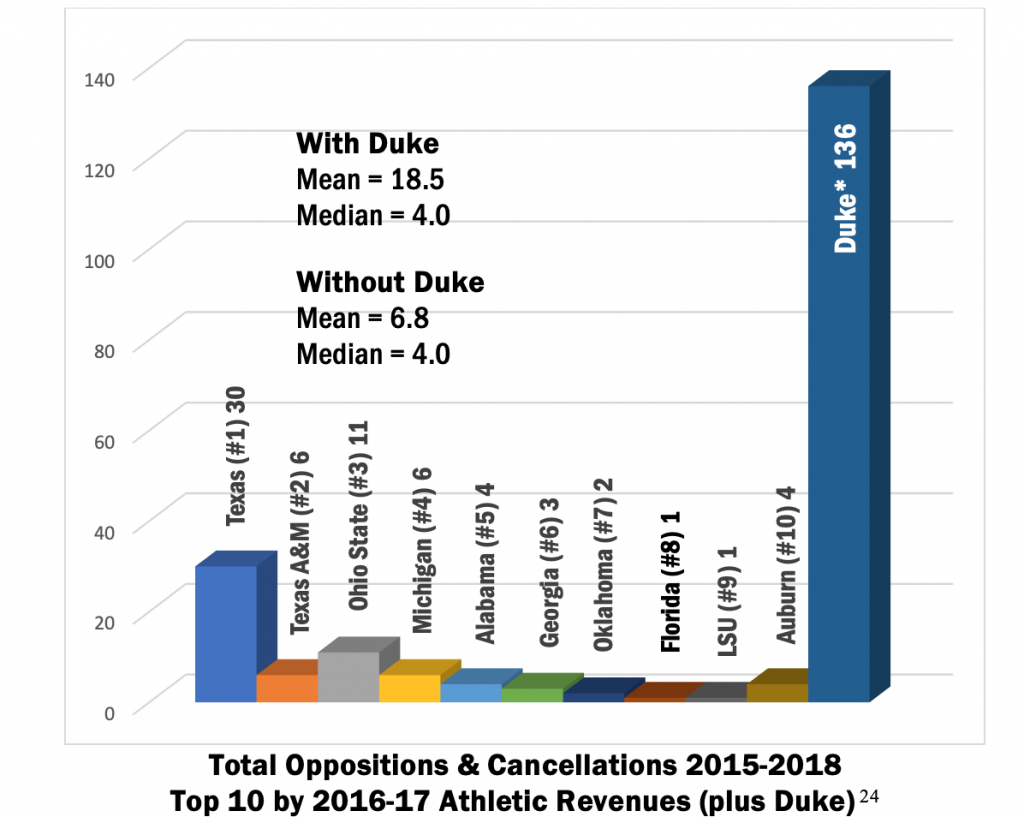

Ok. Well that clearly isn’t the key. How about athletics? Duke has an excellent athletics program, obviously in basketball, but also in a number of other less famous sports. Merchandise is an important part of college sports — for good or ill. We compared Duke to the top ten athletics programs in terms of revenue.

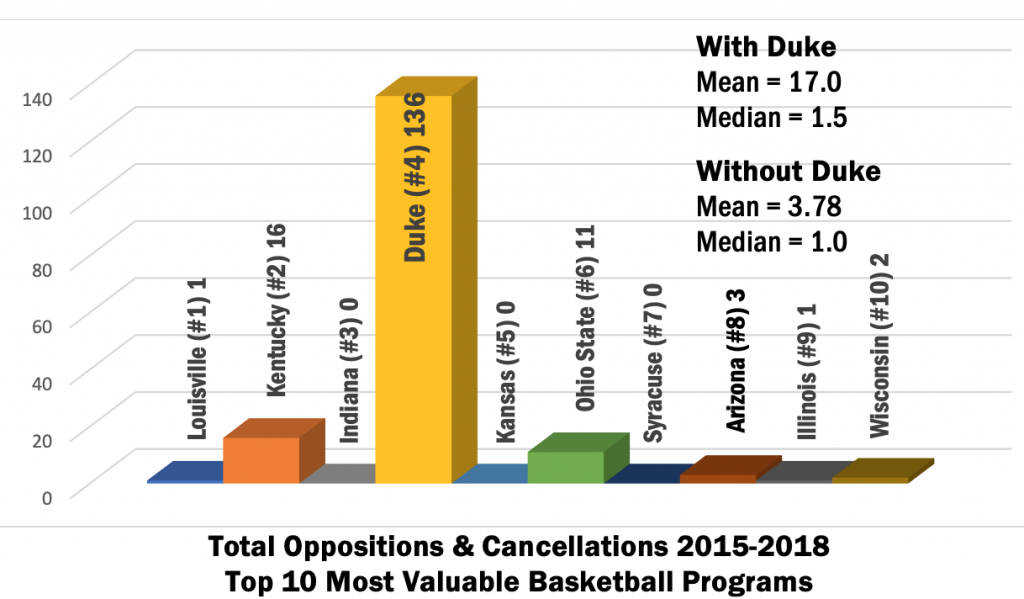

For the first time we can begin to see some increases — Texas at 30 is obviously very assertive — but again there is nothing in Duke’s league. Maybe there is something specific to basketball? Again we went with monetary value of the program rather than some more subjective measure of merit on which sports fans could argue for ever. Revenue, after all, seemed plausibly related to the need to assert one’s marks.

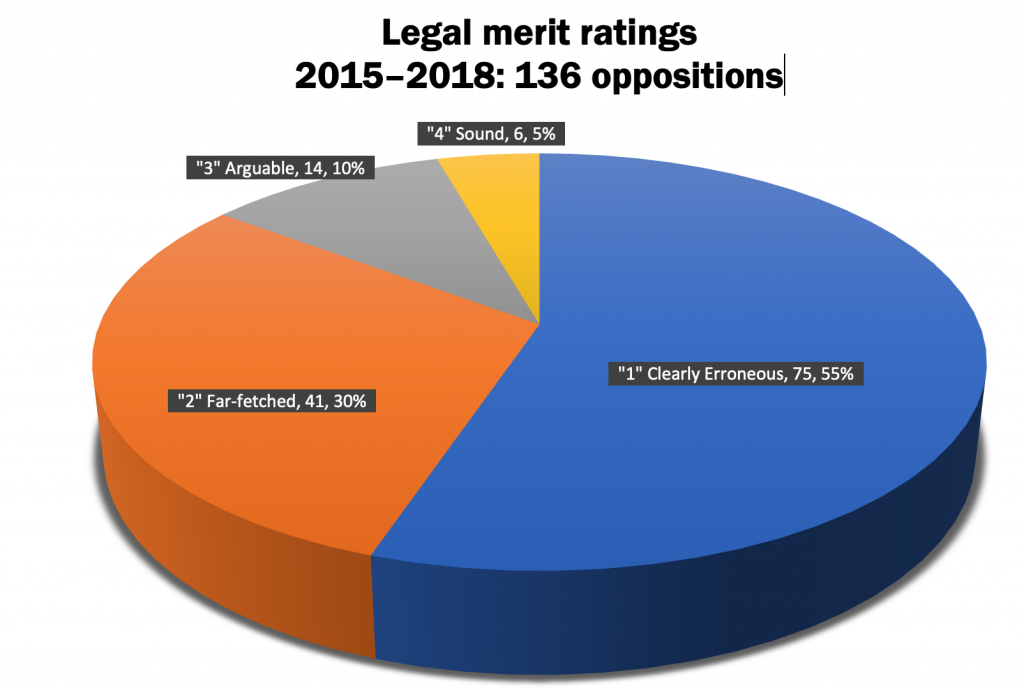

No, that wasn’t it either. In fact, we realized in shock, Duke had filed substantially more oppositions than all of the other universities in our three top ten categories combined. Duke may indeed be “one of the most visible brand names in higher education” but it is hardly more visible than Harvard, Yale, Stanford, MIT, Princeton, Texas, Alabama, Michigan, LSU, Kentucky, Ohio State, Auburn and 16 others put together. Still, perhaps Duke was right about trademark law and all the others wrong? We then hand coded all of Duke’s Oppositions or Cancellations on a four part scale in terms of their quality. The results were not pretty.

An astounding 85% if Duke’s oppositions were either “clearly erroneous” or “far fetched.” To put it another way, if they had only filed the oppositions we had coded as “:sound”, they would have been close to the median in the most assertive comparison group — top athletic programs. Duke is a bully. Wow, what a bully. But our article tries to show that it is an interesting bully — teaching us things about the excesses of modern trademark law and culture, but also about the way in which universities can lose their way when they attempt to turn themselves into mega-brands and licensing factories. What’s more Duke may be a bellwether, boldly bullying, where others will eventually follow. Universities now use over aggressive to police their reputations, even though that far exceeds their real legal rights. Stanford bullied a film company into changing the title of a movie about someone who steals to finance a Stanford education from Stealing Stanford to Stealing Harvard. NYU got the show Felicity from having an NYU student engage in sexual relations while in college: what could be more implausible!? Boise State thinks it owns all non-green football fields. All of thse claims were nonsense, of course, mere bullying, but they represent a disturbing trend.

An astounding 85% if Duke’s oppositions were either “clearly erroneous” or “far fetched.” To put it another way, if they had only filed the oppositions we had coded as “:sound”, they would have been close to the median in the most assertive comparison group — top athletic programs. Duke is a bully. Wow, what a bully. But our article tries to show that it is an interesting bully — teaching us things about the excesses of modern trademark law and culture, but also about the way in which universities can lose their way when they attempt to turn themselves into mega-brands and licensing factories. What’s more Duke may be a bellwether, boldly bullying, where others will eventually follow. Universities now use over aggressive to police their reputations, even though that far exceeds their real legal rights. Stanford bullied a film company into changing the title of a movie about someone who steals to finance a Stanford education from Stealing Stanford to Stealing Harvard. NYU got the show Felicity from having an NYU student engage in sexual relations while in college: what could be more implausible!? Boise State thinks it owns all non-green football fields. All of thse claims were nonsense, of course, mere bullying, but they represent a disturbing trend.

For the details on all of that, you will have to read the article, but here is a taste….

“We think our study also has implications for universities. Are universities straying from their core goals? Corporations have a straightforward metric for action; maximize shareholder value. Universities, by contrast, serve many masters – education, research, the generation and dissemination of knowledge, the preservation of the scholarly commons, the values of free speech and civil debate, the interests of the students, faculty, staff and alumni/ae that make up the university community. It is possible to imagine a world in which a university transforms itself into a mega-brand while, at every stage, continuing to respect those values. In that world, the university gains extra revenue, raises its visibility and stays true to its core mission – a win-win situation. It is also possible, and we would argue, likely, that in areas ranging from aggressive patent licensing practices,[1] to the trademark excesses we document here, to large-scale college athletics,[2] universities have lost their way. The latter comparison may be particularly revealing. Consider the testimony of Sonny Vaccaro to the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics.

“I’m not hiding,” Sonny Vaccaro told a closed hearing at the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C., in 2001. “We want to put our materials on the bodies of your athletes, and the best way to do that is buy your school. Or buy your coach.” Vaccaro’s audience, the members of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics, bristled. These were eminent reformers—among them the president of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, two former heads of the U.S. Olympic Committee, and several university presidents and chancellors…. Not all the members could hide their scorn for the “sneaker pimp” of schoolyard hustle, who boasted of writing checks for millions to everybody in higher education. “Why,” asked Bryce Jordan, the president emeritus of Penn State, “should a university be an advertising medium for your industry?” Vaccaro did not blink. “They shouldn’t, sir,” he replied. “You sold your souls, and you’re going to continue selling them. You can be very moral and righteous in asking me that question, sir,” Vaccaro added with irrepressible good cheer, “but there’s not one of you in this room that’s going to turn down any of our money. You’re going to take it. I can only offer it.”[3]

Being a trademark bully, in other words, is part of a larger transformation about which universities should think long and hard. What is to be done? Our suggestion is a wide-ranging value-audit, in which the university asks a group of internal stakeholders and external advisors to assess the coherence of the university’s various activities with its multiple missions. There are many possible definitions of “mission-creep” but a pretty good one is the point at which a university claims to be in the business of producing goods and services “in virtually all areas of endeavor, to men, women and children of all ages.”

We do not romanticize universities: we work at one. We experience the quotidian idealistic delight and frequent disillusionment of big academe. But we care about universities’ core values Those values seem very strange to the larger society. Why study unpopular ideas? Why care passionately about the truth, even when it doesn’t pay? They are also profoundly fragile. It is possible, of course, that an institution could cherish those values and also become a commercial mega-brand culture with a dubious connection to veracity. We would not take that bet.

Right now, Duke is an anomaly. Will it be one in the future? Perhaps in the domain of trademark oppositions. As we have tried to demonstrate, many of Duke’s trademark oppositions are expensive, legally ungrounded and, while interfering with the legitimate businesses of others, produce little for Duke beyond bad publicity. But what about the wider attempts to use baseless intellectual property claims to police activities universities do not like? There we think that Duke’s aggressiveness might represent the future. We fear, in fact, that Duke is boldly bullying where many universities will eventually follow. We hope this article sounds a warning.

Universities should not be trademark bullies, or for that matter, copyright or patent trolls. If they do not remember this fact, will athletic shoe licensing revenue, satisfaction from stopping an unrelated business from gaining marks they have every right to, claiming ownership of the definite article, or preventing fictional portrayals of sexually active or larcenous students, compensate for the loss? We doubt it. To our university we would quote another Duke, (Ellington) “A problem is a chance for you to do your best.” And, no, we don’t own his name either.

Earlier, we mentioned “the preservation of the scholarly commons” as one of a university’s core goals. At the time of writing, Duke had filed one more trademark. It is over the phrase “Scholarly Commons.” [4] That is exquisite irony, of course. But, as our study shows, it may be disturbingly emblematic of the future of academic intellectual property.”

[1] Mark Lemley, Are Universities Patent Trolls? 18 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 611 (2008).

[2] Gerald Gurney et al, Unwinding Madness: What Went Wrong with College Sports—and How to Fix It. (2017).

[3] Taylor Branch, The Shame of College Sports The Atlantic October 2011.

[4] U.S. Serial No. 87,946,903 (filed June 4, 2018). Now abandoned, thankfully.