Tom Bell is a thoughtful and provocative copyright scholar whose work I follow with interest. On Technoliberation, he has a nice graph showing

a.) the astounding term extensions over the history of copyright in the United States and b.) the way in which they track potential expiration dates for one particular Mickey Mouse cartoon — Steamboat Willie.

What Tom knows, but the casual viewer may not, is that while this graph is quite correct it actually dramatically understates the extent to which the effective length of copyright has been extended and does so in two distinct ways.

1.) For most of American history, copyright has been given in renewable increments. 14 years, renewable for another 14. 28 years, renewable for another 28 and so on. Tom’s graph shows the maximum possible length of copyright at any given time — and does so quite correctly. But if we asked, “what was the median length of actual copyright during that period?” we would have a very different graph. We know that when we finally abandoned the benign practice of renewable terms, 85% of copyright holders were not bothering to renew their works for the second term. Thus, the effective length of copyright for the majority of copyrighted culture was actually half what Tom shows. 14 years in 1790 and so on.

2.) The proportion of culture covered by Tom’s graph changes by several orders of magnitude. Until the 1976 Copyright Act we actually required some formalities before you received a copyright. Those formalities differed through time, but at least this could be said — your work was not copyrighted unless you gave some indication that you wanted it to be (though the requirements of that indication were different). For example, you might have to write “Copyright 1970 James Boyle.” This meant that copyright was an opt in scheme. But after the 1976 Act came into force, copyright was an opt out scheme, and it was hard to opt out. (When we founded Creative Commons, and asked the copyright office how they would recommend putting a work into the public domain, they said “we don’t provide that service.”) What did that mean? Suddenly, all fixed original expression was sucked into copyright, whether you wanted it to be or not. Copyright’s domain increased many hundred fold — in ways that have dramatically impoverished our archival heritage. All those great home movies, journals, neighbourhood newspapers — they are all copyrighted for 95 years or the life of the author plus 70 years. And since we can’t find the authors — they are effectively locked away. We are the first generation that has managed to deny our own culture to ourselves. No work created during your lifetime will, without conscious action by its creator, become available for you to build upon freely without permission or fee. Its a cultural outrage.

Combine those two factors and what do you have? If one looked at effective length of copyright for most works, one would find that a.) for most of American history the vast majority of most potentially copyrightable works weren’t under copyright at all and b.) that, of the tiny, tiny percentage that were, the vast majority went into the public domain at the expiration of their first term. Combine those two factors and the line on the graph becomes dramatically steeper. In fact, it makes Everest look like the Netherlands. We have dragged all of culture into copyright, and kept it there even if the owners wouldn’t have wanted to renew. So, bad as it is, Tom’s graph actually understates the reality.

Term&MMCurve.gif)

Excellent points, both, Jamie! I wholly agree that the graph underestimates the growth in the duration of copyrights in actual practice. I originally pondering trying to illustrate the renewal term, too, but decided it would have unduly complicated the graph. It would prove wonderfully evocative, though, if I could somehow quantify and trace with a single line the effective median copyright term per copyrightable work over time. That would, I think, capture both of the effects you describe.

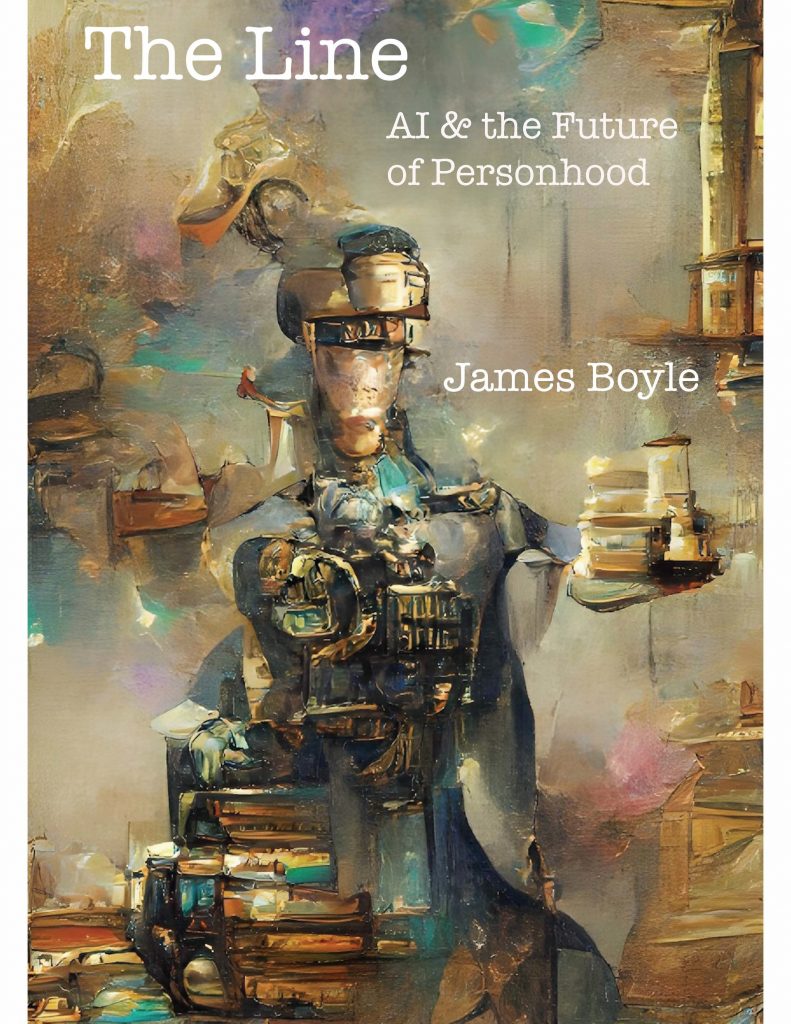

No, I think it was a really useful graph. There’s a constant war between clarity and completeness. I am very much aware of it since I am now writing a comic book about the history of musical borrowing and what it tells us about norms, law, markets and technology…. That turns out to be a somewhat complex topic.

We all aspire to this

https://strangemaps.files.wordpress.com/2007/12/minardmap.jpg

Tufte called it “the best graphic ever” — but personally I’ve never come close.

[…] for individuals and 95 years for corporations; and once 95 years is up, Disney will ask Congress to have it extended to again, and so […]