James Boyle, Oct 25th, 2021

There are a few useful phrases that allow one instantly to classify a statement. For example, if any piece of popular health advice contains the word “toxins,” you can probably disregard it. Other than, “avoid ingesting them.” Another such heuristic is that if someone tells you “I just read something about §230..” the smart bet is to respond, “you were probably misinformed.” That heuristic can be wrong, of course. Yet in the case of §230 of the Communications Decency Act, which has been much in the news recently, the proportion of error to truth is so remarkable that it begs us to ask, “Why?” Why do reputable newspapers, columnists, smart op ed writers, legally trained politicians, even law professors, spout such drivel about this short, simple law?

§230 governs important aspects of the liability of online platforms for the speech made by those who post on them. We have had multiple reasons recently to think hard about online platforms, about their role in our politics, our speech, and our privacy. §230 has figured prominently in this debate. It has been denounced, blamed for the internet’s dysfunction, and credited with its vibrancy. Proposals to repeal it or drastically reform it have been darlings of both left and right. Indeed, both former President Trump and President Biden have called for its repeal. But do we know what it actually does? Here’s your quick quiz: Can you tell truth from falsity in the statements below? I am interested in two things. Which of these claims do you believe to be true, or at least plausible? How many of them have you heard or seen?

The §230 Quiz: Which of These Statements is True? Pick all that apply.

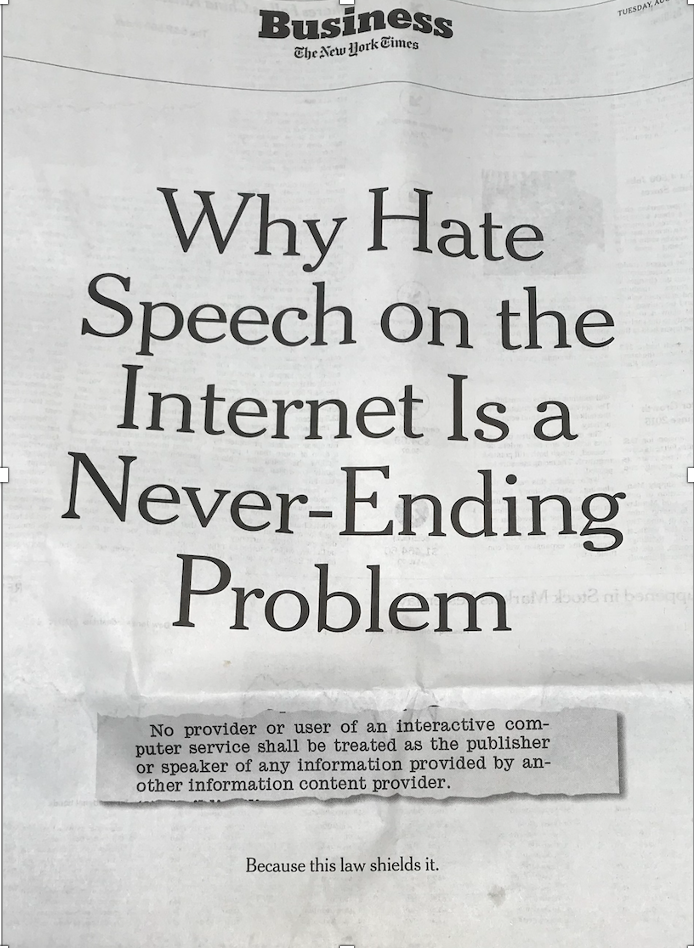

A.) §230 is the reason there is still hate speech on the internet. The New York Times told its readers the reason “why hate speech on the internet is a never-ending problem,” is “because this law protects it.” quoting the salient text of §230.

A.) §230 is the reason there is still hate speech on the internet. The New York Times told its readers the reason “why hate speech on the internet is a never-ending problem,” is “because this law protects it.” quoting the salient text of §230.

B.) §230 forbids, or at least disincentivizes, companies from moderating content online, because any such moderation would make them potentially liable. For example, a Wired cover story claimed that Facebook had failed to police harmful content on its platform, partly because it faced “the ever-present issue of Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act. If the company started taking responsibility for fake news, it might have to take responsibility for a lot more. Facebook had plenty of reasons to keep its head in the sand.”

C.) The protections of §230 are only available to companies that engage in “neutral” content moderation. Senator Cruz, for example, in cross examining Mark Zuckerberg said, “The predicate for Section 230 immunity under the CDA is that you’re a neutral public forum. Do you consider yourself a neutral public forum?”

D.) §230 is responsible for cyberbullying, online criminal threats and internet trolls. It also protects against liability when platforms are used to spread obscenity, child pornography or for other criminal purposes. A lengthy 60 Minutes program in January of this year argued that the reason that hurtful, harmful and outright illegal content stays online is the existence of §230 and the immunity it grants to platforms. Other commentators have blamed §230 for the spread of everything from child porn to sexual trafficking.

E.) The repeal of §230 would lead online platforms to police themselves to remove hate speech and libel from their platforms because of the threat of liability. For example, as Joe Nocera argues in Bloomberg, if §230 were repealed companies would “quickly change their algorithms to block anything remotely problematic. People would still be able to discuss politics, but they wouldn’t be able to hurl anti-Semitic slurs.”

F.) §230 is unconstitutional, or at least constitutionally problematic, as a speech regulation in possible violation of the First Amendment. Professor Philip Hamburger made this claim in the pages of the Wall Street Journal, arguing that the statute is a speech regulation that was passed pursuant to the Commerce Clause and that “[this] expansion of the commerce power endangers Americans’ liberty to speak and publish.” Professor Jed Rubenfeld, also in the Wall Street Journal, argues that the statute is an unconstitutional attempt by the state to allow private parties to do what it could not do itself – because §230 “not only permits tech companies to censor constitutionally protected speech but immunizes them from liability if they do so.”

What were your responses to the quiz? My guess is that you’ve seen some of these claims and find plausible at least one or two. Which is a shame because they are all false, or at least wildly implausible. Some of them are actually the opposite of the truth. For example, take B.) §230 was created to encourage online content moderation. The law before §230 made companies liable when they acted more like publishers than mere distributors, encouraging a strictly hands-off approach. Others are simply incorrect. §230 does not require neutral content moderation – whatever that would mean. In fact, it gives platforms the leeway to impose their own standards; only allowing scholarly commentary, or opening the doors to a free-for-all. Forbidding or allowing bawdy content. Requiring identification of posters or allowing anonymity. Filtering by preferred ideology, or religious position. Removing posts by liberals or conservatives or both.

What about hate speech? You may be happy or sad about this but, in most cases, saying bad things about groups of people, whether identified by gender, race, religion, sexual orientation or political affiliation, is legally protected in the United States. Not by §230, but by the First Amendment to the US Constitution. Criminal behavior? §230 has an explicit exception saying it does not apply to liability for obscenity, the sexual exploitation of children or violation of other Federal criminal statutes. As for the claim that “repeal would encourage more moderation by platforms,” in many cases it has things backwards, as we will see.

Finally, unconstitutional censorship? Private parties have always been able to “censor” speech by not printing it in their newspapers, removing it from their community bulletin boards, choosing which canvassers or political mobilizers to talk to, or just shutting their doors. They are private actors to whom the First Amendment does not apply. (Looking at you, Senator Hawley.) All §230 does is say that the moderator of community bulletin board isn’t liable when the crazy person puts up a libelous note about a neighbor, but also isn’t liable for being “non neutral” when she takes down that note, and leaves up the one advertising free eggs. If the law says explicitly that she is neither responsible for what’s posted on the board by others, nor for her actions in moderating the board, is the government enlisting her in pernicious, pro-egg state censorship in violation of the First Amendment?! “Big Ovum is Watching You!”? To ask the question is to answer it. Now admittedly, these are really huge bulletin boards! Does that make a difference? Perhaps we should decide that it does and change the law. But we will probably do so better and with a clearer purpose if we know what the law actually says now.

It is time to go back to basics. §230 does two simple things. Platforms are not responsible for what their posters put up, but they are also not liable when they moderate those postings, removing the ones that break their guidelines or that they find objectionable for any reason whatsoever. Let us take them in turn.

1.) It says platforms, big and small, are not liable for what their posters put up, That means that social media, as you know it — in all its glory (Whistleblowers! Dissent! Speaking truth to power!) and vileness (See the internet generally) — gets to exist as a conduit for speech. (§230 does not protect platforms or users if they are spreading child porn, obscenity or breaking other Federal criminal statutes.) It also protects you as a user when you repost something from somewhere else. This is worth repeating. §230 protects individuals. Think of the person who innocently retweets, or reposts, a video or message containing false claims; for example, a #MeToo, #BLM or #Stopthesteal accusation that turns out to be false or even defamatory. Under traditional defamation law, a person republishing defamatory content is liable to the same extent as the original speaker. §230 changes that rule. Perhaps that is good or perhaps that is bad – but think about what the world of online protest would be like without it. #MeToo would become… #Me? #MeMaybe? #MeAllegedly? Even assuming that the original poster could find a platform to post that first explosive accusation on. Without §230, would they? As a society we might end up thinking that the price of ending that safe harbor was worth it, though I don’t think so. At the very least, we should know how big the bill is before choosing to pay it.

2.) It says platforms are not liable for attempting to moderate postings, including moderating in non-neutral ways. The law was created because, before its passage, platforms faced a Catch 22. They could leave their spaces unmoderated and face a flood of rude, defamatory, libelous, hateful or merely poorly reasoned postings. Alternatively, they could moderate them and see the law (sometimes) treat them as “publishers” rather than mere conduits or distributors. The New York Times is responsible for libelous comments made in its pages, even if penned by others. The truck firm that hauled the actual papers around the country (how quaint) is not.

So what happens if we merely repeal §230? A lot of platforms that now moderate content extensively for violence, nudity, hate speech, intolerance, and apparently libelous statements would simply stop doing so. You think the internet is a cesspit now? What about Mr. Nocera’s claim that they would immediately have to tweak their algorithms or face liability for antisemitic postings? First, platforms might well be protected if they were totally hands-off. What incentive would they have to moderate? Second, saying hateful things, including antisemitic ones, does not automatically subject one to liability; indeed, such statements are often protected from legal regulation by the First Amendment. Mr. Nocera is flatly wrong. Neither the platform nor the original poster would face liability for slurs, and in the absence of §230, many platforms would stop moderating them. Marjorie Taylor Greene’s “Jewish space-laser” comments manage to be both horrifyingly antisemitic and stupidly absurd at the same time. But they are not illegal. As for libel, the hands-off platform could claim to be a mere conduit. Perhaps the courts would buy that claim and perhaps not. One thing is certain, the removal of §230 would give platforms plausible reasons not to moderate content.

Sadly, this pattern of errors has been pointed out before. In fact, I am drawing heavily and gratefully on examples of misstatements analyzed by tech commentators and public intellectuals, particularly Mike Masnick, whose page on the subject has rightly achieved internet-law fame. I am also indebted to legal scholars such as Daphne Keller, Jeff Kosseff and many more, who play an apparently endless game of Whack-a-Mole with each new misrepresentation. For example, they and people like them eventually got the New York Times to retract the ludicrous claim featured above. That story got modified. But ten others take its place. I say an “endless game of Whack-a-Mole” without hyperbole. I could easily have cited five more examples of each error. But all of this begs the question. Why? Rather than fight this one falsehood at a time, ask instead, “why is “respectable” public discourse on this vital piece of legislation so wrong?”

I am a law professor, which means I am no stranger to mystifying error. It appears to be an endlessly renewable resource. But at first, this one had me stumped. Of course, some of the reasons are obvious.

- “I am angry at Big Tech because (reasons). Big Tech likes §230. Therefore, I am against it.”

- “I hate the vitriol, stupidity and lies that dominate our current politics. I hate the fact that a large portion of the country appears to be in the grips of a cult.” (Preach, brother, preach!) “I want to fix that. Maybe this §230 lever here will work? Because it looks “internet-ty” and the internet seems to be involved in the bad stuff?”

- “I know what I am saying is nonsense but it serves my political ends to say it.”

I share the deep distrust of the mega-platforms. I think that they probably need significantly more regulation, though I’d start with antitrust remedies, myself. But beyond that distrust, what explains the specific, endlessly replicated, fractal patterns of error about a simple law?[1] I think there is an answer. We are using §230 as a Rorschach blot, an abstraction onto which we project our preconceptions and fears, and in doing so we are expressing some fascinating tendencies in our political consciousness. We can learn from this legal ink-blot.

The Internet has messed up the public/private distinction in our heads. Analog politics had a set of rules for public actors – states or their constituent parts – that were large, enormously powerful and that we saw as the biggest threats in terms of endless disinformation (Big Brother in 1984) and repressive censorship (ditto). It also had a set of rules for private actors – citizens and companies and unions. True, the companies sometimes wielded incredible power themselves (Citizen Kane) and lots of us worried about the extent to which corporate wealth could coopt the public sphere. (Citizens United.) But the digital world introduced us to network effects. Network effects undercut the traditional liberal solutions: competition or exit. Why don’t you leave Facebook or Instagram or Twitter? Because everyone else is on there too. Why don’t you start a competitor to each of them? Same reason. Platforms are private. But they feel public. Twitter arguably exercised considerably more power over President Trump’s political influence than impeachment. What are we to make of that? We channel that confusion, which contains an important insight, into nonsensical readings of §230. Save the feeling of disquiet. But focus it better

The malign feedback loops of the attention economy reward speed, shallowness, and outrage. (Also, curiosity and Tiktok videos.) The algorithms only intensify that. They focus on what makes us click, not what makes us think. We rightly perceive this as a huge problem. The algorithms shape our mental nourishment the same way that Big Fast Food shapes our physical nourishment. Our health is not part of the equation. The people who are screaming “This is big! We need to focus on it right now!” are correct….

…but it’s not all bad. We need to recognize that the same networks that enabled QAnon, also enabled #Metoo and Black Lives Matter. Without the cell phone video of a police stop, or the tweet recounting sexual harassment, both connected to a global network, both demanding our attention, we would not have a vital megaphone for those who have been silenced too long. §230 makes possible a curated platform. It cannot guarantee one. (No law could. Read Daphne Keller on the problems of content-moderation on a large-scale basis.) It lets users post videos or experiences without the platform fearing libel suits from those pictured, or even suits from those whose postings are removed. 30 years ago that was impossible. The “good old days” were not so good in providing a voice to the silenced. Still, much of what we have today is awful and toxic. The temptation is to blame the dysfunction on an easy target: §230. Fixing the bad stuff and keeping the good stuff is hard. Mischaracterizing this law will not aid us in accomplishing that task. But knowing what it does say, and understanding why we mischaracterize it so frequently, well, that might help.

James Boyle © 2021 This article is licensed under a Creative Commons, Attribution, Non-commercial, Sharealike license. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 I am indebted to the work of Mike Masnick, Daphne Keller and Jeff Kosseff, together with many others. Thanks for your service.

[1] The pertinent parts of §230 are these: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider… No provider.. shall be held liable on account of.. any action voluntarily taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected.” [Emphasis added] Not so hard, really? Yet all the errors I describe here persist.