There have been some hiccups with the accessibility of my new Financial Times column.. which (ironically) is about accessibility.. Here it is.. (and thanks to the excellent Financial Times people who let me keep the copyright to my columns and allow me to put my own copies of those columns under a CC license)– check out the other people they have writing on intellectual property, communications, and the internets.

Obama in cyberspace

By James Boyle

For those stalwarts who lived through the Bush years in a thrall of horror and disbelief, broken only by Jon Stewart monologues, Barack Obama’s arrival has been cathartic. True, the sight of your retirement account statement may bring on nausea, chills and palpitations. (Is it really unrealistic to think of working until you are 70? As a bicycle messenger?) But there is always the soothing relief of hearing the announcement that yet another Bush policy has been overturned, even if the announcement generally comes with a pragmatic footnote. America is now against torture again. (But also against prosecuting those who tortured and against declassifying photos of abuse.) Guantánamo will be closed down. (Though we don’t know quite where the inhabitants will go.) The United States will do something about climate change. (Even though the actual plan is full of corporate giveaways.) The phrase ”Justice Department” no longer sounds like an oxymoron. And so on.

Sometimes the ”pragmatism” looks a little like ”not trying” – as when Obama scurried quickly into retreat on immunity for the telephone companies who participated, probably illegally, in spying on US citizens. But those who understand politics better than I give him fairly high marks on his combination of principle and pragmatism. And since I couldn’t craft a legislative majority at a dinner table over what Chinese food to order, I am reluctant to throw stones at those who have to deal with considerably more unwieldy coalitions.

So what does Obama’s mixture of principle and pragmatism look like in the world of the new economy, and more specifically, the world of intellectual property policy? The picture is definitely mixed. On the one hand, he has brought brilliant people to important positions. It is nice to have a Nobel prize-winner (Steven Chu) as Secretary of Energy, and another (Harold Varmus) as the Co-chair of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. It is hard to imagine the Obama team talking about science as if it were simply one inconvenient partisan position or ridiculing the ”evidence based mindset” or, for that matter, evolution itself. The administration has good ideas about what to do with the slow motion train-wreck that is the US Patent and Trademark Office. It is not clear if those good ideas will be implemented, but one can hope. In the area of copyright law . . . well, the signs are mixed.

Traditionally, Democratic administrations take their copyright policy direct from Hollywood and the recording industry. Unfortunately, so do Republican administrations. The capture of regulators by the industry they regulate is nothing new, of course, but in intellectual property there is the added benefit that incumbents can frequently squelch competing technologies and business methods before they ever come into existence. Years of making policy this way have given us retrospectively extended copyright terms that are in excess of 100 years. (Perpetual copyright ”on the instalment plan” in Peter Jaszi’s words.) It has given us a one-sided and unbalanced view of the world, which registers with complete accuracy the real dangers that the content industry faces from any new technology, while ignoring the benefits those same technologies can provide – including to the content industry. The Obama administration’s warm embrace of Silicon Valley, and Silicon Valley’s chequebook, had given some hope that this pattern would change – and I think it will. Now, instead of taking copyright policy direct from the media conglomerates (who, after all, have a very legitimate point of view – even if not the only point of view) it is quite likely that the administration will construct it as a contract between content companies and high-technology companies such as Google. In some places, citizens and consumers will probably benefit, simply because optimising for the interests of two economic blocs rather than one is likely to give us a slightly more balanced, and less technology-phobic, set of rules. And perhaps the administration will go further. But recent actions make me doubt that this is the case.

First, the administration’s messages about the so-called copyright czar have left little doubt that it is the content industry that is going to be commanding the cossacks. (Would you really want to be called a “czar”? We don’t have a patent tyrant, or an antitrust dictator, so why a copyright czar? But I digress) The goal of the law that created this position is simple. It is to give unprecedented high-level governmental representation to the interests of a particular set of industries, so they can, ahem, help ensure that other agencies, such as the Justice Department put the appropriate resources and zeal into prosecuting DVD pirates and handbag counterfeiters. One wouldn’t want them to be confused about their priorities after all. (Even the Bush administration Justice Department, which historically thought nothing except gay marriage was constitutionally suspect, managed to perceive that this was a tad problematic if one believed in prosecutorial independence.) Obama isn’t responsible for this silly law. But he does control who fills the position. So far as I can tell, the debate has now shifted to precisely how dogmatic the representation of intellectual property holders should be. The idea that intellectual property policy might actually require a balance between multiple interests, including some who are not rights holders, has apparently been abandoned. If a few thoughtful scholars such as Larry Lessig get caricatured in the process, well, what’s the harm?

But the final straw may be the Obama administration’s opposition to a proposal on copyright exceptions for the visually impaired. About 95 per cent of books are not available for blind or partially sighted readers. Some countries have exceptions in their laws which, very sensibly, condition the grant of the copyright monopoly on a (very) few public interest limitations, such as the right to make non-commercial versions of works one has legally purchased in order to make them accessible to the visually impaired. (For example, generating a machine-readable audio book, or a Braille version, from a legally purchased digital text.) The proposal would generalise and harmonise those exceptions. It is backed by a number of developing countries and opposed – quietly – by the US and most of the European Union. Hip-deep in a colossal market failure on a global scale, they say optimistically that the market will provide an acceptable solution, though there is overwhelming empirical evidence that it will not.

Why oppose this proposal? Scaremongering aside, there is no real threat to anyone’s business model here. But if one sees any limitation of the most extreme version of copyright as a dangerous and ideologically driven attack on property itself, well then, one must fight. This proposal represents the ideas that rights should have limits and that we should harmonise limitations and exceptions as well as rights themselves. It is that principle, the principle of balance, that must be resisted. Even if it puts one in the embarrassing position of – ever so pragmatically – sacrificing one’s blind citizens to an industry agenda. In a world where we have to deal with torture and climate change and the collapse of our economic system, this little piece of moral cowardice is not something many people are going to notice. But it leaves a nasty taste in the mouth, nonetheless.

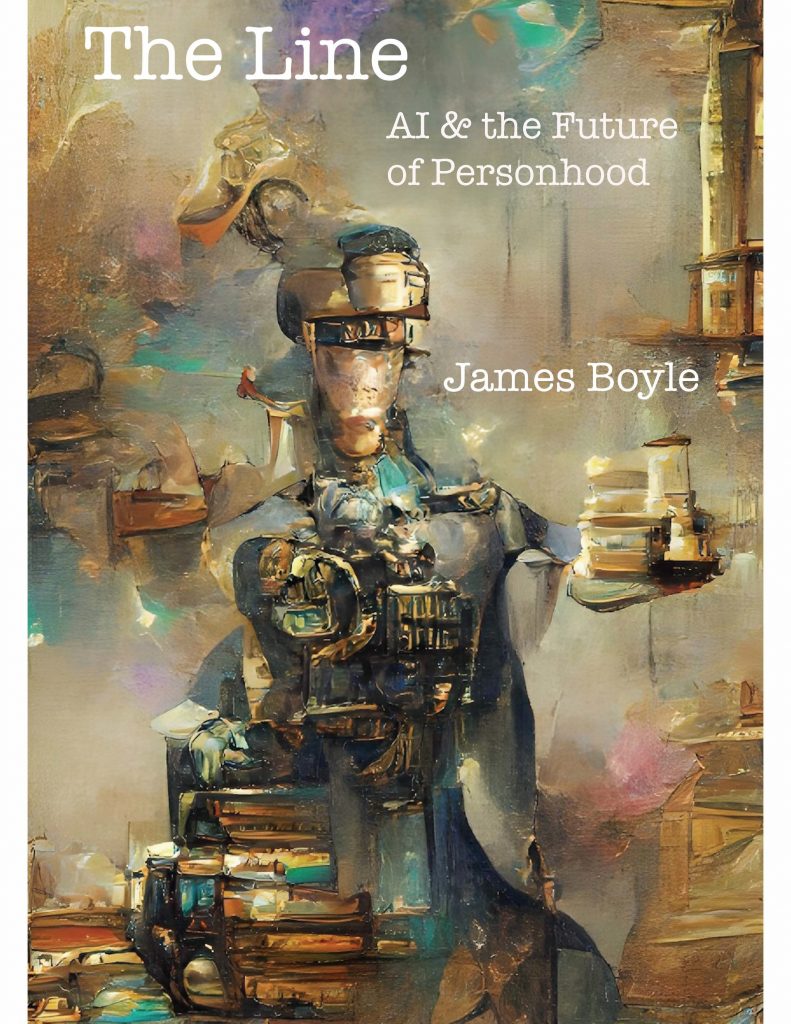

James Boyle is a professor of law at Duke Law School. His most recent book is The Public Domain: Enclosing the Commons of the Mind.

Even setting aside for the moment that there is no such thing as “Intellectual Property” in the United States, let alone any so called property rights even involved; there are some limited time privileges that congress MAY choose to grant, there is nothing in article I which even says congress MUST actually do so, I am curious how one constructs the idea of for example copyright cartels seeking exclusive and unlimited rights to cultural artifacts as being legitimate? At best, it seems like arguing that Al Capone had a very legitimate point of view on filing taxes.

Some suggest the U.S. constitution offers the idea as a kind of balanced social contract between the public interest and that of creative producers. This idea does not strike me as abhorrent in itself, and indeed that could be offered as a very legitimate viewpoint. However, the fundimental problem is that middlemen are now choosing to entirely renegotiate the terms of said contract after the fact into a one sided contract of adhesion. Applying the word “legitimate interest” to that seems far more than merely inappropriate, it perpetuates a fraud.

For it to be a case of moral cowardice, opposition to the proposal would have to be accompanied by awareness that such opposition is unjustified.

Thanks for the comment. Since I have spent most of my career being portrayed as a foe of everything the content industry holds dear, I am savouring the experience of /. readers thinking I am an apologist for the same industry ;-> The entire article criticizes the Obama administration for adopting too closely the views of the content industry, for sending signals that they will pick as a copyright czar someone who serves the interests of that industry and, in an act of “moral cowardice”, giving up the interests of blind and visually impaired citizens to serve that agenda. On what do the slashdot comments focus? One single phrase that suggests that the content industry actually has a legitimate point of view. This is perhaps an example of ignoring the forest and focusing on a single twig?

For 20 years I have written at far too great a length the reasons why I think the view of the content industry is mistaken. I think it is profoundly wrong and the legislation that has propounded it is in some cases unconstitutional. But the fact that I disagree with it and think it mistaken does not make it *illegitimate as a view.* That is an important point in, and a defining feature of, a liberal democracy.

Here’s a discussion of my use of the term “intellectual property” https://www.movingtofreedom.org/2008/11/30/james-boyle-the-public-domain/

And as for the “breaking the deal” point — that was actually the title of an earlier article about the shameful practice of retrospective copyright term extension. If you are interested, the book this site is devoted to contains a lengthy explanation of why the Jeffersonian view of copyright is superior to that of the content industry, why the Framers of the constitution might be appalled by the system set up under Article 1 section 8 clause 8, while ignoring that clause’s limitations, and why the path they have taken is precisely the wrong one.

But to return to the main point — I’d at least hope for an equal amount of outrage at what is being done to the interests of visually impaired citizens, or in the appointment of the copyright czar.

(And re PL Hayes’ point on moral cowardice, I agree. And I think it was.)

“On what do the slashdot comments focus? One single phrase…..”

That is precisely why i never read the comments on /.

I read the post, the referenced articles or blogs, and move on with life.

I thoroughly enjoyed what you had to say here, and fully agree.

Thanks for the clarification. I’ve read – with admiration – your FT pieces and watched your google tech. talk video etc. but I’m not surprised the /. readers got hold of the wrong end of the stick. It’s rarely worth reading beyond the /. front page these days.

[…] 3: Obama in cyberspace […]

I appreciate your ongoing support for accessibility for blind and visually impaired readers. We are a “low incidence” population, as the sociologists say. We’re likely to remain marginalized on most others’ moral horizons, but we may serve here as canaries in the coal mine.

Thanks Mark. Much appreciated and https://fairuselab.net/ is a great initiative. Congratulations!