In Ray Bradbury’s 1953 classic, Fahrenheit 451, a “fireman” is a man who burns books “for the good of humanity.” Written at the height of the Cold War, the book paints a shockingly dystopian picture of a culture at war with its own printed record, one deeply infused by Bradbury’s love of books. When the book was written, Bradbury got a copyright term of 28 years, renewable for another 28 years if he or his publisher wished. Most authors and publishers did not bother to renew — very few have a commercial life longer than a few years. That meant that about 93% of books and 85% of all works from 1953 passed into the public domain within 28 years. But Bradbury’s book was a commercial success. The copyright was renewed and as a result it would have been entering the public domain tomorrow — January 1, 2010 — Public Domain Day.

In Ray Bradbury’s 1953 classic, Fahrenheit 451, a “fireman” is a man who burns books “for the good of humanity.” Written at the height of the Cold War, the book paints a shockingly dystopian picture of a culture at war with its own printed record, one deeply infused by Bradbury’s love of books. When the book was written, Bradbury got a copyright term of 28 years, renewable for another 28 years if he or his publisher wished. Most authors and publishers did not bother to renew — very few have a commercial life longer than a few years. That meant that about 93% of books and 85% of all works from 1953 passed into the public domain within 28 years. But Bradbury’s book was a commercial success. The copyright was renewed and as a result it would have been entering the public domain tomorrow — January 1, 2010 — Public Domain Day.

You could reprint it, make a low cost educational version, legally create a braille or audio book edition, even base a new film or play on it. All without asking permission or paying a fee. But copyright law has changed since then. Copyright terms have been twice retrospectively extended. Now, Fahrenheit 451 is not slated to enter the public domain until 2049.

You could reprint it, make a low cost educational version, legally create a braille or audio book edition, even base a new film or play on it. All without asking permission or paying a fee. But copyright law has changed since then. Copyright terms have been twice retrospectively extended. Now, Fahrenheit 451 is not slated to enter the public domain until 2049.

For Bradbury’s book, this means that the reading public, the braille printer, the budding playwright, the school library face either higher prices, or legal restrictions on reuse or both. And they get no benefit from it. Clearly, the incentive of 28 + 28 years was enough to encourage him to write the book and the publisher to publish it. The evidence is that.. it happened. Retrospectively extending copyright is deadweight social loss — harm without benefit. But at least the book is available.

But the legal changes introduced in the years after Fahrenheit 451 did more than just extend terms. Congress eliminated the benign practice of the renewal requirement (which had guaranteed that 85% of works and 93% of books entered the public domain after 28 years because the authors and publishers simply didn’t want or need a second copyright term.) And copyright, which had been an opt-in system (you had to comply with some very minor formalities to get a copyright) became an opt out system (you got a copyright automatically when you “fixed” the work in material form, whether you wanted it or not.) Suddenly the entire world of informal and non commercial culture — from home movies that provide a wonderful lens into the private life of an era, to essays, posters, locally produced teaching materials — was swept into copyright. And kept there for the life of the author plus 70 years. The effects were culturally catastrophic. Copyright went from covering very little culture, and only covering it for a 28 year period during which it was commercially available, to covering all of culture, regardless of whether it was available — often for over a century. Unlike Fahrenheit 451, the vast majority of the culture swept into this 20th century black hole was not commercially available and, in most cases, the authors are unknown. The works are locked up — with no benefit to anyone — and no one has the key that would unlock them. We have cut ourselves off from our own culture, left it to molder — and in the case of nitrate film, literally disintegrate — with no benefit to anyone. The works may not be physically destroyed — although many of them are; disappearing, disintegrating, or simply getting lost in the vastly long period of copyright to which we have relegated them. But for the vast majority of works and the vast majority of citizens who do not have access to one of our great libraries, they are gone as thoroughly as if we had piled up the culture of the 20th century and simply set fire to it; and all this right at the moment when we could have used the Internet vastly to expand the scope of cultural access. Bradbury’s firemen at least set fire to their own culture out of deep ideological commitment, vile though it may have been. We have set fire to our cultural record for no reason; even if we had wanted retrospectively to enrich the tiny number of beneficiaries whose work keeps commercial value beyond 56 years, we could have done so without these effects. The ironies are almost too painful to contemplate.

January 1st 2010 — and every January 1st — is public domain day, the day we celebrate the entry of copyrighted works into the public domain. In the United States no published work will pass into the public domain tomorrow — nor the next year, nor any year until 2019. (If you lived in Europe you might now be celebrating the release of the works of Freud or Yeats.) Thus, we have little to celebrate, and many costs to mourn. Its sad to look at the works that could be entering the public domain today.

January 1st 2010 — and every January 1st — is public domain day, the day we celebrate the entry of copyrighted works into the public domain. In the United States no published work will pass into the public domain tomorrow — nor the next year, nor any year until 2019. (If you lived in Europe you might now be celebrating the release of the works of Freud or Yeats.) Thus, we have little to celebrate, and many costs to mourn. Its sad to look at the works that could be entering the public domain today.

Groups around the world are using Public Domain Day as a way to explain the effects of our copyright system on our collective culture. (Communia’s site and the Public Domain Works registry deserve special attention.) ) For more details about Public Domain Day go to the Center for the Study of the Public Domain’s Public Domain Day Website, or visit our Frequently Asked Questions page. And happy Public Domain Day, and Happy New Year, to all of you.

Oh bull. Most “creative re-use” is just ripping off the original artist. Those “budding playwrights” can dream up their own ideas, rather than glomming on to Bradbury’s. I think that a sliding scale for reprints and education (which usually falls under Fair Use, anyway) makes sense, but allowing works of art–by a still living writer, artist or filmmaker–to be open to the ravages of any clod with a keyboard is disrespectful and foolish.

Orphan works are a different kettle of fish, I’ll grant. But for you and other professors to decide that Ray Bradbury should just give away the rights to his work is pretty high-handed. If you wrote anything as classic as Fahrenheit 450, you might feel differently. It’s easy to call for an end to copyright when it’s not your work at stake.

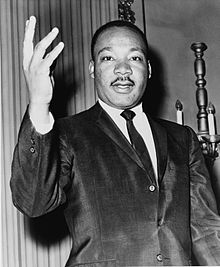

Thanks Kate. I don’t think what you say is “bull” but I do disagree on both points. First, I am not at all saying Ray Bradbury should “give away” the rights to his work. I am saying that he originally wrote Fahrenheit 451 with the promise of 56 years of copyright. I see nothing unfair in holding him and other authors to that bargain – the copyright term offered when they created the work. If I agreed to paint your fence for $10 — painted it — and then asked for $20 and you insisted on only paying me the original $10, would you say you were asking me to “give away” my labor? There is no credible argument in favor of retrospective copyright term extension. Second, on creative reuse — sure there are hack reusers, just as there are hack original creators. But without the freedom to reuse without permission or payment, we lose Ray Charles’ soul music. https://yupnet.org/boyle/archives/130#20 And we lose a lot more. “Artists of all kinds — writers, musicians, filmmakers, painters — rely on the public domain: “Poetry can only be made out of other poems, novels out of other novels,” as the critic Northrop Frye put it. Creators draw on previous works, and on the cultural artifacts around them; they remix vintage footage with new clips, turn books into plays and musicals, borrow lyrics and melodies from old songs, adapt classic stories to present day circumstances. Over the holidays, you may have enjoyed the new critically acclaimed Sherlock Holmes movie — an adaptation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s public domain work. Or your children may have been transfixed again by Disney’s beloved Snow White, Pinocchio, and The Little Mermaid, which are based on public domain works by The Brothers Grimm, Carlo Collodi, and Hans Christian Anderson. As Judge Richard Posner observed, if the underlying works were copyrighted, “Measure for Measure would infringe Promos and Cassandra, Ragtime would infringe Michael Kohlhaas, and Romeo and Juliet itself would have infringed Arthur Brooke’s The Tragicall Historye of Romeo and Juliet . . . which in turn would have infringed several earlier Romeo and Juliets, all of which probably would have infringed Ovid’s story of Pyramus and Thisbe.” The creative fruits of the public domain are all around us.” https://www.law.duke.edu/cspd/publicdomainday/whyitmatters So, no I don’t see anything unfair in holding Bradbury (whose work I love) to his original term and then letting the process of creative reuse that we have used as a species for the rest of our cultural history, take its course. To put the question the other way round, what limits would you set. Must copyright last forever? Must each person be forbidden from building on any other cultural creation?

Thanks again for your comment.

I really enjoyed reading this piece as Fahrenheit 451 was one of my favorite books in high school and the irony of modern day commercialism and it’s entanglement with the government.

I believe that the copyright term limits need to be revised to ensure cultural integrity as well as benefiting the authors legacy. I would think the current limit is too much however I do believe that an author should be paid if the reproduction or use of his work during his lifetime is used for commercial purposes. I understand that there are different definitions of “commercial purpose” but a cultural/historical definition should be defined to enrich and not diminish the value or the cultural time of the work as it was created.

[…] https://www.thepublicdomain.org/2009/…ne-by-lawyers/ […]

Sorry, James,

but most of your own examples definitely don’t support your original idea.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle died 1930

Wilhelm Grimm died 1859, Jacob Grimm died 1863

Carlo Collodi died 1890

Hans Christian Andersen died 1875

The 70 years after death-copyright obviously didn’t do anything to hurt or suppress or hinder the progress and evolvement of art or creativity in the cases you mentioned.

And you don’t need a creative work in public domain to be influenced by it and include this influence in your own work. Simply read it, watch it, listen to it and extract what seems inspirational to you – without being a rip-off. The least any original artist could and would ask for, no matter what and how long the coypright is.

Sorry, James I cannot be as polite as you toward this troglodyte.

KateC,

Who gives a damn about “new” and “unique” and “creative”. It’s a creative work not laundry detergent. You hip firing self righteous illiterate busybody mosquitoes claim to be standing up for authors – bah check out what the publishers make, some friend of the originator you are – or for innovation – because something new and entirely devoid of context and therefore, value, is supposedly of some use – but you’re nothing but a glorified armchair grammar Nazi who specializes in superficial opinions on rights and progress.

Let me make it clear to you: The value of any creative, productive, or moral work is what IT ADDS! Not what it is. Newton’s calculus is valuable because it ADDS to previous efforts in mathematics and physics. Flannery O’Connor allegedly said there really are only three stories and she was damn right on the money.

The value of a work is not the flavor of the month fragile NOVELTY or the fad of the week ENTERTAINMENT facet, both of which fade far sooner than 28 years. The value of a creative, productive, or moral work is how IT USES familiar FORMS. That’s why we have the public domain so that an author can give their creative, productive, and moral OPINION on SOCIETY through ART.

Authors use other people’s work in order to CONTINUE the CONVERSATION and DEBATE that LIVES INSIDE the work. Go play with your American Idol action figures. People like you disgust me. You have not even the slightest clue as to why people write (it ain’t about their selfish “precious” feelin’s, hon) yet you support a crusty parasitical and hysterical policy.

The reason you fidgety, fickle, channel surfing, boob tube products don’t understand the value of anything beyond its 15 minutes currency is because you poseurs only chase (hypocrites) after the value determinations of others a habit you picked up from those cynical echo chamber miniature casinos known as public schools. Nothing wrong with attending them, but plenty wrong with not resisting the inertia and brain damage they inflict.

It has to be minty fresh and shiny like a ring tone or you illiterates won’t even give it notice.

Art is about examination NOT RANDOM self-stroking “unique expression”. I appreciate those who break new ground, in well known topics which are so well known that important difficult to construct SUBTLE DETAILS can peek out from under potentially DISORIENTING pedantically fresh flourishes.

KateC, you’re just a bored book reader. You don’t actually follow the work of any author despite claiming to care.

New is worthless because it says nothing about things that matter. Retreads are extremely important because they teach us something “new” about the things we think we know so well.

Let toddlers worry about their “new” toys. Copyright prevents DISCUSSION through narrative.

Hi Thomas. Yes all those are legal. Um, for me to give an example of someone famously and successfully building on the works of others, it pretty much has to be legal, no? And if its legal, then you could say that the copyright term didn’t prevent this example. But the point is not that, the point is what about all the other examples that we DON’T see because they were prevented. If you want examples of works that were created in the past and would be illegal under today’s law, Shakespeare s a good starting place and there are plenty more in the book. I’d suggest the Ray Charles story. https://yupnet.org/boyle/archives/130 Thanks for your interest.

It also means that Ray, who is still alive and writing actively, will still get some payment for the brilliance of his work.

You want a poster child for this, pick Mickey Mouse.

[…] neu das privateigentümliche Copyright auf Bücher und Text ausläuft. James Boyle schildert am Beispiel von Bradburys 1953 erschienen Klassiker Fahrenheit 451, wie es der […]

An author does not write to express latent unresolved teenage self-concept problems.

An author creates to extend the library of culture not inflate it with the “new” and “unique” and “special”.

Extending the total body of requires revisiting and reusing old forms.

Copyright prevents reuse which prevents refinement and cultural relevance even.

Copyright therefore is a general harm. Those who argue that any one instance is proof of no harm, deliberately choose the worthless novelty line of argument which demeans the history of literature and the authors who created it.

[…] he would have renewed his copyright, tomorrow is the day that Ray Bradbury’s Farenheit 451 would have gone into the public domain under the law as it was before 1976. But now it won’t be. Instead of the “book […]

I see no justification for longer copyright terms for artists than what engineers and inventors get in the form of patents (17-21 years or so). The only reason they have that is that they are, practically by definition, better at writing propaganda for their interests. Cry me a river for the artist upset with the use that their work is put to after the expiration of their 20ish year copyright. Do you think the inventor of the TV would have liked the use that his marvel of engineering was often put to?

[…] published in 1953 and would once have been entering the public domain on January 1, 2010. To quote James Boyle, “Bradbury’s firemen at least set fire to their own culture out of deep ideological […]

Excellent argument. Thank you.

The biggest casualties of the public domain lockdown are the film/multimedia works created at that time. Up until 1934 a lot of amazing films were produced. If the 75 year rule were still in effect, we’d have most of the major works by Harold Lloyd, some Marx Brothers films, the film All Quiet on the Western Front and a lot of others. (Next year Fred Astaire’s Top Hat would have gone into the public domain). Videographers today would love to have access to an extra 10 years of stock footage to make their films or documentaries.

As for literary texts, the biggest effect is that it makes students pay more for textbooks. Here in Texas, one of our most noted literary texts, Dorothy Scarborough’s The Wind was published in 1925 and out of print. (I wrote about it here ). A teacher cannot easily assign this book for class without scrambling for overpriced used copies. One result of this is that literary works for which mass-produced copies are available (i.e., Great Gatsby) continue to be assigned in classes and lesser known works continue to be overlooked. Also, lots of critical works were published between 1922 and 1934; it would have been great to be able to access full copies of them on Google Books. Instead, we must burden the Interlibrary Loan system (one estimate was that in terms of manpower and resources, ILL requests cost a city library $10-20 per request). These are real costs that city libraries have to suck up and pay.

Ok, I’ll try again with the URL

https://www.teleread.org/2007/01/01/welcome-to-1922-againand-again/

One other thing. In the ebook publishing business I’m in, locking down public domain for 20 years makes it a lot harder to track down images of paintings which were originally published in art books. Indie publishers frequently rely on illustrations from public domain paintings for their publications. If we had 12 more years of material from published art books, that would improve the amount and variety of illustrations we can use. (On a good note, Wikipedia has implemented a good system of labeling public domain art).

[…] Passend dazu: Fahrenheit 451… Book burning as done by lawyers […]

[…] Boyle on his Public Domain […]

[…] Story here. […]

[…] Millones de libros perdidos en el olvido por culpa del copyright [EN] http://www.thepublicdomain.org/2009/12/31/fahrenheit-451-book-burni… por Elwing hace 3 segundos […]

Great post and some great comments. I think the most important point in this case is that the extensions of copyright have become so commonplace that we have completely forgot the reason for its existence. As Anti Vigilante points out, the value of creative work is its contribution to the intellectual commons.

The reason copyright exists is solely for the purpose of encouraging innovation, that was one of the primary reasons the Copyright Act of 1790 established the rights of individuals to a total of 28 years of protection. Anything beyond that original idea of copyright makes no sense as a means for encouraging contributions to society and culture. In fact anything longer than that has a stifling effect.

Someone above mentioned Mickey, who is the critical figure in this whole argument. The copyright extensions have nothing to do with authors: most of them are dead. They have to do with the corporations who had nothing to do with the creation of the work, or of ANY work, but simply bought the rights after the fact and started panicking years later when their investment was about to suffer.

Just like with music… the artists don’t get a frick’ing DIME of the money the RIAA brings in with their lawsuits that re based on “protecting artists rights”.

Bring back the 28 year copyright.

Or as Woodie Guthrie put it (via Cory Doctorow)

This song is Copyrighted in U.S., under Seal of Copyright #154085, for a period of 28 years, and anybody caught singin it without our permission, will be mighty good friends of ourn, cause we don’t give a dern. Publish it. Write it. Sing it. Swing to it. Yodel it. We wrote it, that’s all we wanted to do.

[…] Original source : https://www.thepublicdomain.org/2009/12/31/fahrenhe… […]

[…] at the moment when we could have used the Internet vastly to expand the scope of cultural access. Fahrenheit 451… Book burning as done by lawyers (Thanks, Jamie!) (Image: Burned Book a Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike image from […]

[…] nuevo sobre los títulos descatalogados, podéis ver esta entrada de The Public Domain y los comentarios en castellano en menéame, que dan una buena idea de las posturas, opiniones y […]

I’ve wrote about this in my blog (in Spanish) before (https://recreoanacronista.wordpress.com/2009/09/12/los-manuscritos-el-pdf-y-la-poetica-de-aristoteles/).

Many things will be lost, as when the written word appeared, but with some differences: now it’s not the lack of resources, it’s not the lack of interest, it’s the laziness of the propietors.

This may sound a radical idea for many, but I think that copyright should be only been avalaible when the book, for example, is avalaible for purchase. When it’s impossible to get a copy, the propietor of the rights it’s renouncing “de facto” to make profit for it, so I don’t understand why should this right be enforced still for the remaining time (in Spain I think it`s around 80 years…).

The copyright it’s clearly a menace for the survival of the works, as it denies the possiblitity of spreading them, but also doesn`tworry about their survival after the copyright has expired. And why should them?

[…] Fahrenheit 451… Book burning as done by lawyers […]

Dear Charlie Martin, you say “It also means that Ray, who is still alive and writing actively, will still get some payment for the brilliance of his work.”, but this is wrong, to say the least.

Copyright (as most or all rights) is not something an individual “has”, but something the society *gives* her. It is not a right born with the person, it is a right conceded by the society to its individuals, with the *sole* *purpose* of supporting culture. Copyright does not exist to make authors wealthy, as patents do not exist to make inventors wealthy. They exist to create an incentive for authors and inventors to release their work to the community, having a way of taking economical advantage of it. If this implies becoming wealthy, great, but the objective of the law is that they release their job, not that they get rich, or even make a living.

Bradbury clearly had enough incentive to write, trivially proven by the fact that he *did* write. It would be perverse to use copyright law to benefit him further, instead of benefiting the community further. And it is really perverse to make the society believe that copyright law has this aim.

Nice One…….

[…] Fahrenheit 451… Book burning as done by lawyers But the legal changes introduced in the years after Fahrenheit 451 did more than just extend terms. Congress eliminated the benign practice of the renewal requirement (which had guaranteed that 85% of works and 93% of books entered the public domain after 28 years because the authors and publishers simply didn’t want or need a second copyright term.) And copyright, which had been an opt-in system (you had to comply with some very minor formalities to get a copyright) became an opt out system (you got a copyright automatically when you “fixed” the work in material form, whether you wanted it or not.) Suddenly the entire world of informal and non commercial culture — from home movies that provide a wonderful lens into the private life of an era, to essays, posters, locally produced teaching materials — was swept into copyright. And kept there for the life of the author plus 70 years. The effects were culturally catastrophic. […]

[…] 12, 2010 · Leave a Comment Jaime Boyle posted earlier this month noting that Ray Bradbury’s Farenheit 451 would have entered the […]

[…] Shared Fahrenheit 451… Book burning as done by lawyers | The Public Domain |. […]

This is a debate that has been going on for many years. I think Spider Robinson best expressed what is my opinion on the subject in a story he wrote, Melancholy Elephants (which can be found on his website at https://www.spiderrobinson.com/melancholyelephants.html). In it, he presents a very good expression of why copyright must be allowed to expire. And to be blunt, it is the corporations, such as Disney, that want to keep extending copyright in perpetuity. Not the writers.

[…] Shared Fahrenheit 451… Book burning as done by lawyers | The Public Domain |. […]

[…] Doctorow su Boing Boing riprende un articolo in cui Jamie Boyle denuncia i lati oscuri delle leggi sul copyright. In particolare, gli effetti […]

[…] Doctorow su Boing Boing riprende un articolo in cui Jamie Boyle denuncia i lati oscuri delle leggi sul copyright. In particolare, gli effetti […]

[…] use but with no author or estate to uphold the responsibilities of ownership. The result, as The Public Domain spells out, is a sort of 20th century cultural black hole in which practical access to almost […]

[…] Fahrenheit 451… Book burning as done by lawyers Fahrenheit 451… Book burning as done by lawyers: […]

[…] burning might be out of fashion, but thepublicdomain.org argues here that gradual changes to copyright law over the past fifty years are accomplishing the same […]

[…] Groups around the world are using Public Domain Day as a way to explain the effects of our copyright system on our collective culture. (Communia’s site and the Public Domain Works registry deserve special attention.) ) For more details about Public Domain Day go to the Center for the Study of the Public Domain’s Public Domain Day Website, or visit our Frequently Asked Questions page. And happy Public Domain Day, and Happy New Year, to all of you. Статья Джеймса Бойла о вреде 70-тилетнего срока копирайта thepublicdomain.org […]

All published works are in the public domain.

Copyright is an unethical 18th century anachronism to be ignored by anyone who recognises the individual’s natural right to liberty and the injustice of privilege that suspends it.

By copying and improving upon each other’s work is how Homo Sapiens has progressed for aeons. To submit to the corrupt legislation that prohibits it is a dereliction of one’s duty to mankind.

Share and build upon mankind’s cultural heritage without fear or hesitation.

@Crosbie,

“Copyright is an unethical 18th century anachronism to be ignored by anyone who recognises the individual’s natural right to liberty and the injustice of privilege that suspends it.”

No. Just… no.

Copyright is a necessary compromise between the culture and the creative.

It is intended to give the creative enough reward to produce more creative stuff. Take that away and many creators will stop creating.

Or, to put it another way, it should allow the creative to do anything, but not enough for them to do nothing.

The problem is that it has gone way too far in the other direction. The copyright mob sound like Gollum: “It’s ours forever, my precious..!” Somebody needs to tell these folks “NO”.

[…] Namen. Und aktuell nicht nur zentrales Element der Kultur, sondern auch des Kulturkampfes gegen repressives und infinites Copyright — in welchem wir uns, gesellschaftlich und individuell, die Rechte an unserer eigenen Kultur […]

[…] i att 98% av alla upphovsrättsbelagda inte är tillgängliga för att man inte vet vem som har rättigheterna till dem. Samma problem finns i Europa och Sverige, men allt eftersom upphovsrättstiden utökats så har […]

Interesting discussion. But remember one thing: many, many books written after 1922 but before 1964 are in the public domain, because the copyrights were never renewed.

The automatic renewal only applies to post-1963 works. Before that, if they weren’t renewed after their first 28 years, that’s too bad– they’re in the PD. And as for films and TV, pre-1964, if they were not registered and deposited with the Library of Congress, they could NOT be renewed until that was done.

So, a mere notice on one of these works– or someone now claiming that they were previously unpublished, so they are copyrighting it now– is not valid. They are in the full PD.

The issue of copyright is a lot older than America. It’s a compromise. Authors are not creative in a vacuum. They are part of our culture. The guys that wrote constitution knew this.

The constitutional language of this reflects that intellectual property is the property of the public, but that to encourage creativity for a limited period creators had the right to control and make money for their work. They did this because they had problems with their former governments giving all intellectual property rights to monied interests.

The new laws, in order to be constitutional are not forever. They are “forever minus one day”.

I’m sure 100 years from now when our popular culture, literature and music becomes public domain, that it will have long since been destroyed.

Because of this law, who we are today will be lost in time. The copies we have of our music and movies will have long since turned to dust and no one can archive them.

The majority of the movies that entered the public domain after 28 years are “lost films”. What will happen after 100?

Anyhow.. I run retrovision.tv and so I keep my eye on what is going on with the public domain. We gave it all away to save Mickey Mouse for Disney.

Maybe we should have made a special law. It’s what they did for A. Hitchcock in the UK.

If it was that important for Disney to keep Mickey out of the public domain, we should have done something less detrimental to history.