What if you could own the facts of the news?….. Would that save the news industry?

Hot news: The next bad thing

By James Boyle

Published: March 31 2010 23:03 | Last updated: March 31 2010 23:03

Entrepreneurs and venture capitalists spend a lot of time trying to figure out the next big thing; the new trend, product or web service that will take us by storm. Intellectual property scholars are a little different. We spend a lot of time wondering about the next bad thing.

What will be the latest empirically ungrounded expansion of rights, conferring monopoly rents on market incumbents with scant regard to unintended consequences?

Recent hearings on the future of the news industry at the US Federal Trade Commission (full disclosure: I was an invited participant) signalled the arrival of a new candidate. Newspapers are lobbying for a new federal intellectual property right over “hot news.” European equivalents have also been proposed.

Sadly, the “hot news” right is not as racy as it sounds. It does not offer legal protection for scantily clad celebrities. This is a legal right that extends far beyond copyright law to cover the facts of the news themselves; if I break the story, the hot news right allows me to stop competitors from repeating the facts – at least for as long as the story has immediate currency.

The right has existed in US state common law since a 1918 case called International New Services v. Associated Press. The British government did not like the sceptical coverage of the First World War by US newspapers owned by Randolph Hearst (the real life Citizen Kane). It banned them from using the transatlantic cables to report the news – an early 20th century version of the Great Firewall of China. In the process, the British government conveyed an effective monopoly of European coverage on the Associated Press.

Seeking to get around that monopoly, but also interested in making a buck, Hearst’s International News Services resorted to getting early editions of AP newspapers, or taking news from bulletin boards, collecting the facts and rewriting the stories with their own particular editorial slant. None of these acts were violations of copyright law. The case went to the Supreme Court which held that there could be a “quasi property right” (which is legal jargon for “we just made this thing up”) in hot news, at least against AP’s competitors.

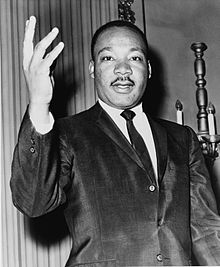

Holmes and Brandeis – two of the most famous Supreme Court Justices of the 20th century – both dissented. Brandeis famously commented that the general rule of law was that knowledge and ideas, the “noblest productions of the human mind” should, after voluntary communication to others, be “free as the air to common use.”

Brandeis lost this one. Still, the effects were not huge. The hot news doctrine became a relatively limited right in a few states – including New York. It was occasionally invoked, often to obviously anti-competitive ends, such as unsuccessful attempts to claim that sports leagues “own” the scores from those leagues and can prohibit others revealing them. But because of constitutional limitations on what states can do to affect the choices made by Federal copyright law, its impact was relatively small,

Fast forward 90 years. The newspaper industry is struggling in the online world. You might think that it is not struggling because its content is being illicitly copied but because it has no good business model to make money off entirely licit, legal uses of its content. The momentary eyeball tracks across news pages just do not translate into enough subscriptions, advertisement clicks, or classified ad sales. You would be right.

In some cases newspapers have lost business because other services now do things better than they did – E-Trade, Edmunds.com or Zoopla provide more in depth information on mutual funds, cars or houses for sale than the sections of the newspaper devoted to them ever could. In the process, those sites take the lucrative targeted advertisements with them.

In other cases, the new services do things more cheaply – Craigslist classified advertisements is an example. And finally, the method of delivery changes the time readers spend on the news pages. Hal Varian – chief economist at Google – presented data at the FTC hearing showing that people read the news largely at work, sixty or ninety seconds at a time, hardly long enough to make much money with advertisements. His data also showed that the current collapse in revenues from subscription and advertising is part of a long term trend that began long before the web.

This is a complex reality. It may be that new business models – subscription sites, links to new devices such as the Kindle and the iPad – can revive newspapers. It may be that we will develop other methods to support investigative journalism – interesting experiments are already under way. But it would be an enormous diversion to let these struggles somehow convince us that the newspapers’ ills are the result of illicit copying and can be cured by yet another new intellectual property right.

Yes, there are legal aggregation sites – such as Google news – which contain short snippets of news stories. If newspapers want their content removed from these sites they can do so easily by simply changing the data contained in something called the robots.txt file. Google or Yahoo will no longer index their pages.

But the newspapers do not want to do this, because legal aggregators drive a great deal of traffic to them. And in any event, they do not need a new right to stop the practice. There are also sites that do illegally copy the entire contents, or the entire article. Their behaviour is already illegal under copyright law. (And in any event has a small effect on revenues. Do you read the FT stories at some shady site or at the FT?)

So the new right would have no effect on the real problem newspapers face. And it would give them almost no protection that they do not already have either through law or technology. What would it do? It would cast a pall of fear over free speech. Is my blog or twitter feed allowed to say that there has been an earthquake or that some political scandal has erupted? Or must I buy a license to say so? After all, in the new world bloggers are “competitors” as news sources.

In fact, the right would produce all kinds of effects the newspapers have not thought about. They are assuming that this new right will only be wielded by them. Not so. Think of political activists who break a story – for example the young conservative filmmakers who produced devastating information on the operation of the organization ACORN. They are a news source. They might think it was a great idea selectively to decide which news organizations got to report that story, at least as long as it was “hot.” Does that sound attractive? I think not. And then think of the difficulties of proof, the possibility of chilling of speech by wrongly claiming to be its source. Implementation would be a nightmare.

So there it is. Our next bad idea. In some ways it shares many characteristics with other recent expansions of intellectual property law. It is unsupported by data and it has unintended and anti-competitive consequences. The sad difference is that newspapers truly do face a wrenching future and the debate over how to pay for high quality investigative journalism is an important one. Unfortunately, the hot news right would do nothing to help solve the real problems newspapers face.

Instead, it would do much to impede the benign effects that the internet has on news gathering and distribution and to chill the social media that will surely be part of the marketplace of ideas in the future. The negative effects of a new legal monopoly without even the benefits to the current market incumbents! Which is what makes the proposal all the more poignant.

The nice folk at the Financial Times, where I write a column, have an enlightened attitude towards copyright. When they arranged for me to be a columnist, they agreed to let me keep the copyright and to make articles available under a Creative Commons license. This is one of my recent columns for the FT. If you find it of interest, you might want to reward them by checking out https://www.ft.com/techforum There is lots more there.

News, as we know it, is dying. Just as Paper-based encyclopedias gave way to CD-ROMS which gave way to the Internet (can you say “Wikipedia”?)

The meteor has hit. The Dinosaurs will soon be extinct. And the world will change. That is the way of things.

[…] Hot news: The next bad thing Yes, there are legal aggregation sites – such as Google news – which contain short snippets of news stories. If newspapers want their content removed from these sites they can do so easily by simply changing the data contained in something called the robots.txt file. Google or Yahoo will no longer index their pages. […]

[…] lawyers pushing for the return of hot news, or for other forms of copyright to protect news, may end up regretting that before too long. Beyond the fact that full copying is already illegal under copyright law and the lack of any […]

[…] to discourage Stoklasa from filing a counter-notice. The videos, however, have been restored.3: Hot news: The Next Bad ThingFinally today, commentator James Boyle has some thoughts on “Hot News”, a legal […]

[…] Hot news: The next bad thing Sadly, the “hot news” right is not as racy as it sounds. It does not offer legal protection for scantily clad celebrities. This is a legal right that extends far beyond copyright law to cover the facts of the news themselves; if I break the story, the hot news right allows me to stop competitors from repeating the facts – at least for as long as the story has immediate currency. […]

[…] tam tikrą laiką nuo įvykio aprašyti jį tiems, kas nespėjo pirmieji. Tačiau ne veltui žmonės juokiasi iš sumanymo – žurnalistas (beveik) niekada nebūna arčiausiai įvykio – arčiausiai įvykio būna žmogus […]